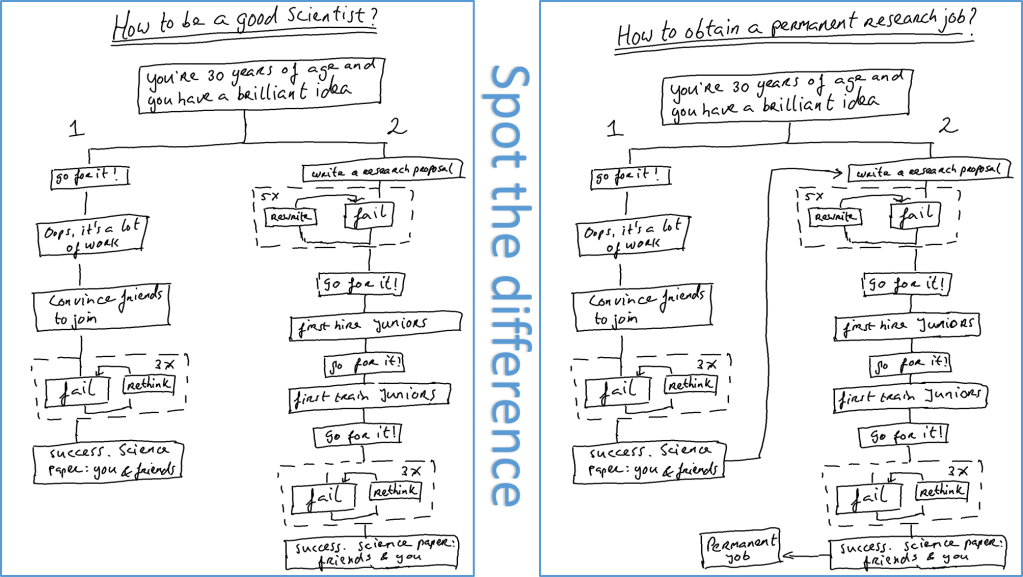

Many good PhD-students leave science for a job in industry nowadays. Some do, because they really want to explore the big world out there. But others do, because they know the path to a permanent research job can be a frustrating money hunt, with little time for the real fun: use your brilliant brains and do the science yourself. These considerations made me draw a sketch last week. Please have a look below. Apologies for my bad handwriting!

Science is top sport

The left diagram illustrates that both branch 1 (doing) and 2 (managing) are legitimate ways to obtain nice scientific results. But it seems the appreciation for the latter vastly exceeds that of the former nowadays. Because – as the big arrow in the right diagram shows – if you choose to follow branch 1, it implies a big detour towards a permanent job. Hence, already at the end of their PhDs, students are pushed to write grant proposals or take a course on this. And we know: due to likely repetative failures this costs a lot of time. So, these bright brains are not optimally used for what they are good at: doing science. This is, in my opinion, very sad. Science is top sport. Did we ask Rafael Nadal to become a tennis coach after his first Roland Garros win? Did we ask Mathieu van der Poel to become the manager of a cycling team after his glorious win in the Amstel Gold Race? I’m very glad we didn’t.

Struggling statisticians

My own field, biostatistics, faces an extra hurdle when trying to obtain a grant. It is interdisciplinary by definition. I like that a lot! But satisfying two communities in one proposal (damn those word counts) is superhard, because the biologist says: “this is too technical, you should focus more on applications”, whereas the statistician says: “you need to give more details on the methods”. I have been lucky to strike the right balance a few times now, but it has taken me a while to find it. I am happy that I was given the time to develop my own ideas and gain experience on where I am in the spectrum.

Granting time

I really hope that we are moving back to a system in which that valuable time is also granted to nowadays young scientists. I put my hopes on Robert Dijkgraaf, formerly at Princeton, now minister in the Dutch government. I’m pretty sure that he values branch 1 as much as branch 2.

Sources

Main image: commons.wikimedia.org; pixabay.com

Add comment